Salesforce’s Head of AI Sees Digital Labor Revolution

AI and digital labor will transform work

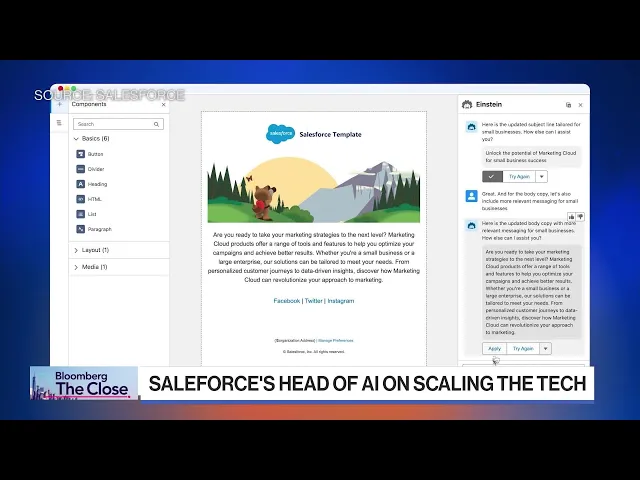

In the rapidly evolving landscape of artificial intelligence, few voices carry the weight and insight of Salesforce's Head of AI. During a recent interview, they shared compelling perspectives on how AI is fundamentally reshaping our relationship with work, setting the stage for what they term a "digital labor revolution." This isn't merely another incremental technological shift, but rather a profound transformation in how we conceptualize productivity, value creation, and the very nature of work itself.

Key insights from the conversation:

- AI is evolving from a productivity tool to a form of "digital labor" that can autonomously perform complex tasks that previously required human judgment and creativity

- This transition will necessitate rethinking organizational structures, job definitions, and the economic value of both human and digital contributions

- The coming decade will likely see AI systems moving from assistive roles to increasingly autonomous agents capable of independent decision-making

The digital labor paradigm shift

The most striking insight from the interview is the framing of AI not just as tools but as a new form of labor. This represents a fundamental shift in how we should conceptualize these technologies.

Traditional productivity tools augment human capabilities—they make us faster, more efficient, more accurate. But they remain fundamentally extensions of human intent and control. What Salesforce's AI head envisions is something qualitatively different: systems that don't just assist but actively perform work with minimal human supervision.

This matters tremendously because our entire economic and organizational structures are built around human labor as the primary productive force. When machines can not only execute physical tasks but also perform knowledge work—making judgments, synthesizing information, creating content, and even innovating—we enter uncharted territory.

Consider how we currently organize businesses: hierarchies of human decision-makers, supported by tools. But what happens when the "tools" can make decisions? The implications ripple through everything from compensation structures to organizational design to economic policy.

The unexplored territories

What the interview doesn't fully address are the messy transition challenges as we move toward this digital labor future. Drawing from historical labor transitions, we can anticipate significant friction points.

Take the legal profession as an example. AI is already dramatically changing document review, contract analysis, and case research—tasks that traditionally occupied junior associates. Law firms face difficult questions: How do they train

Recent Videos

How To Earn MONEY With Images (No Bullsh*t)

Smart earnings from your image collection In today's digital economy, passive income streams have become increasingly accessible to creators with various skill sets. A recent YouTube video cuts through the hype to explore legitimate ways photographers, designers, and even casual smartphone users can monetize their image collections. The strategies outlined don't rely on unrealistic promises or complicated schemes—instead, they focus on established marketplaces with proven revenue potential for image creators. Key Points Stock photography platforms like Shutterstock, Adobe Stock, and Getty Images remain viable income sources when you understand their specific requirements and optimize your submissions accordingly. Specialized marketplaces focusing...

Oct 3, 2025New SHAPE SHIFTING AI Robot Is Freaking People Out

Liquid robots will change everything In the quiet labs of Carnegie Mellon University, scientists have created something that feels plucked from science fiction—a magnetic slime robot that can transform between liquid and solid states, slipping through tight spaces before reassembling on the other side. This technology, showcased in a recent YouTube video, represents a significant leap beyond traditional robotics into a realm where machines mimic not just animal movements, but their fundamental physical properties. While the internet might be buzzing with dystopian concerns about "shape-shifting terminators," the reality offers far more promising applications that could revolutionize medicine, rescue operations, and...

Oct 3, 2025How To Do Homeless AI Tiktok Trend (Tiktok Homeless AI Tutorial)

AI homeless trend raises ethical concerns In an era where social media trends evolve faster than we can comprehend them, TikTok's "homeless AI" trend has sparked both creative engagement and serious ethical questions. The trend, which involves using AI to transform ordinary photos into images depicting homelessness, has rapidly gained traction across the platform, with creators eagerly jumping on board to showcase their digital transformations. While the technical process is relatively straightforward, the implications of digitally "becoming homeless" for entertainment deserve careful consideration. The video tutorial provides a step-by-step guide on creating these AI-generated images, explaining how users can transform...